Leveraging Title I funds for teacher capacity building is a strategic financial model where districts utilize Title I, Part A allocations to finance job-embedded professional development and instructional coaching.

Authorized by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), this approach allows schoolwide programs to divert funds from general operations to specific teacher effectiveness interventions, which research shows drives student achievement more than class-size reduction.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) authorizes schoolwide programs to invest in content-focused professional development and coaching. These programs can fund job-embedded learning that directly improves instruction. This guide shows how to leverage Title I strategically for teacher capacity building.

Key Takeaways

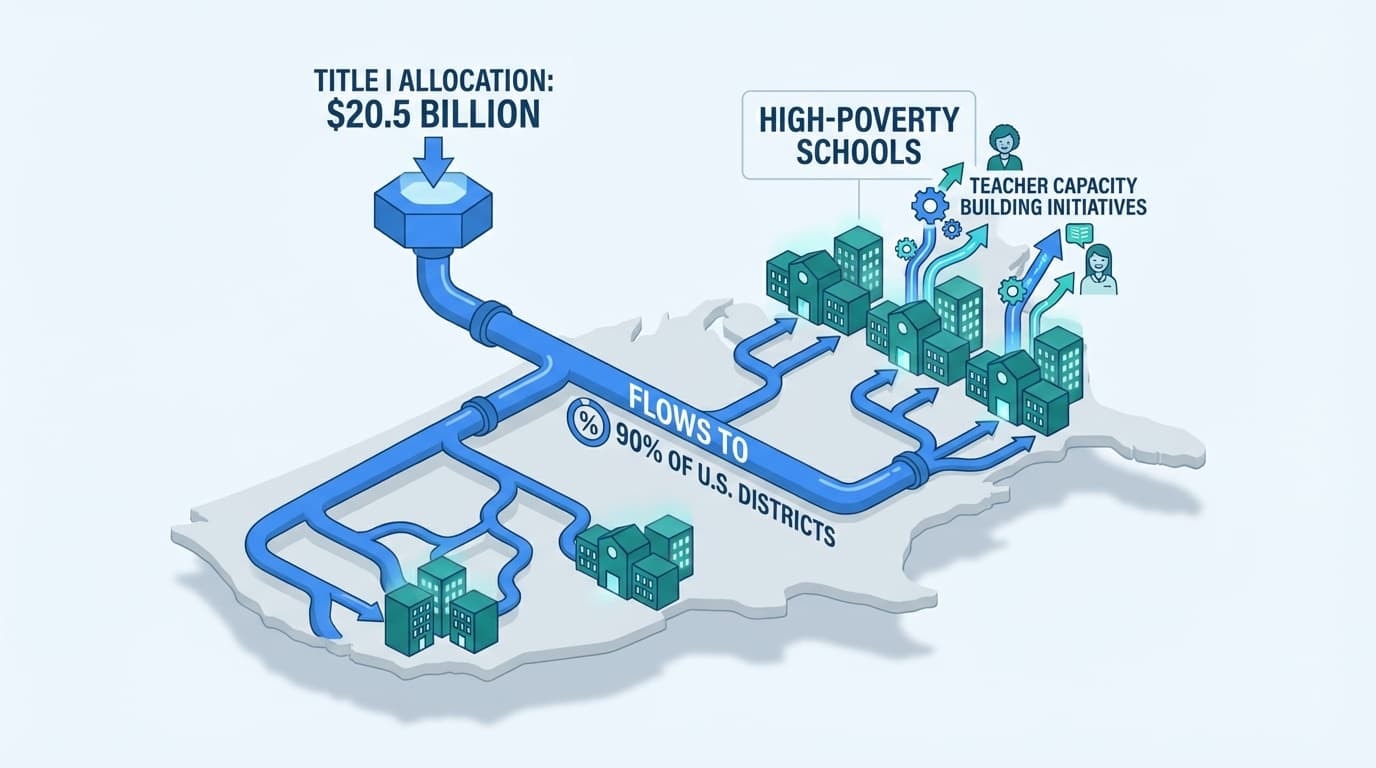

- FY2024 Title I, Part A funding reached $20.5 billion and serves roughly 90% of all U.S. districts, dwarfing the $2.25 billion available through Title II.

- ESSA allows Title I schoolwide programs to have specific flexibility to fund job-embedded professional development and coaching, as long as the activities align with comprehensive support and improvement plans.

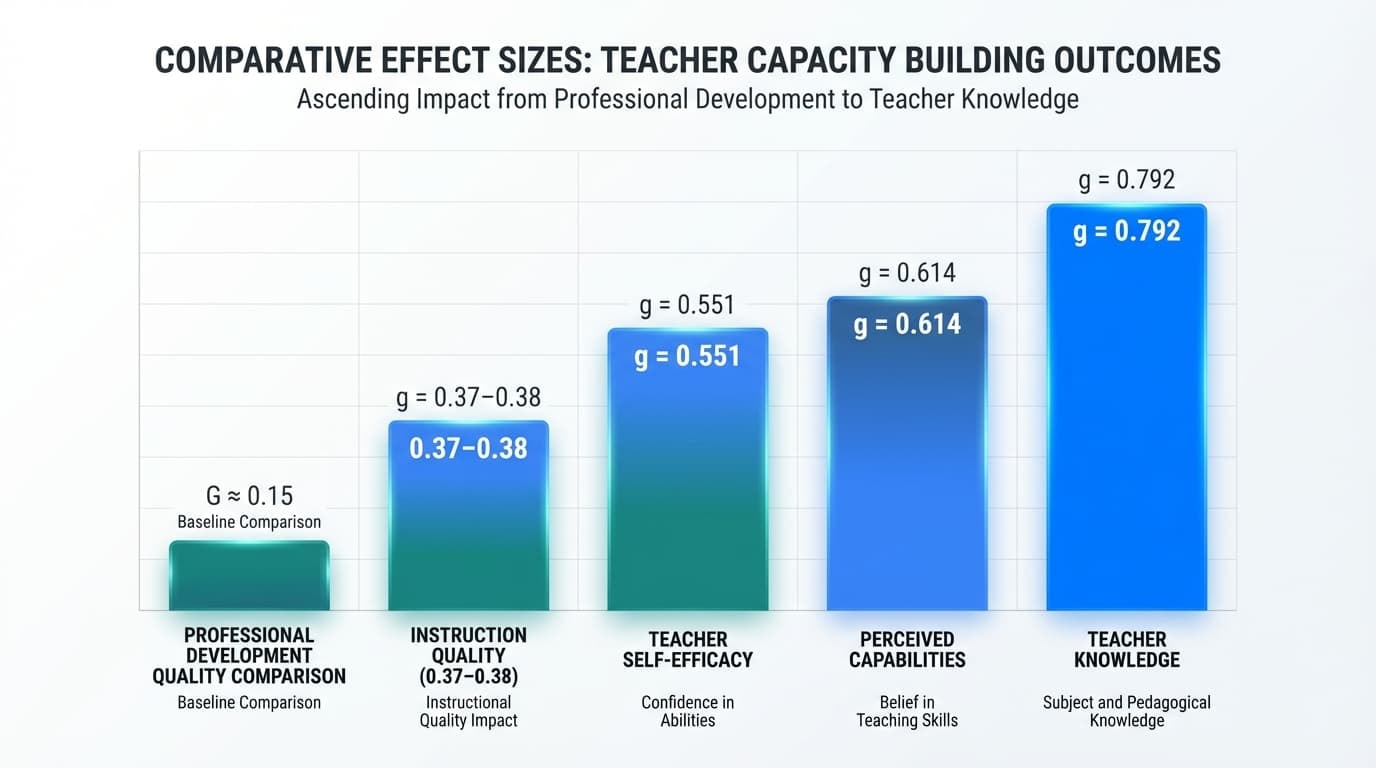

- Research shows capacity building can produce an effect size of g = 0.792 for teacher knowledge, with teacher self-efficacy gains of g = 0.551–0.614 across studies, directly improving students’ academic achievement.

- Effective Title I–funded development includes coaching cycles, professional learning communities, and lesson study; content-focused learning on core subjects significantly outperforms traditional workshops.

How Does Title I Function as a Lever for Teacher Capacity?

Title I functions as a lever for capacity building by providing roughly $20.5 billion annually (FY2024) to 90% of U.S. districts, specifically authorizing schoolwide programs to upgrade educational quality through comprehensive professional development.

Title I, Part A allocates federal resources to high-poverty schools using statutory formulas based on census poverty data, ensuring financial support reaches students facing unique systemic barriers.

Teacher effectiveness matters more than class-size reduction, making capacity-building investments highly cost-effective for achievement. Every dollar spent on teacher growth produces long-term returns for students.

For FY2024, Title I appropriations reached approximately $20.5 billion, as reported by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), a figure that dwarfs the $2.25 billion allocated to Title II, Part A.Title I’s scale dwarfs other professional development sources.

Studies have shown that schoolwide programs typically serve schools where at least 40% of students come from low-income backgrounds. These programs offer flexibility to upgrade entire educational programs, including comprehensive professional development and instructional coaching.

ESSA explicitly allows Title I funds to support teacher learning, including developing instructional leaders and improving teaching. Section 1114 authorizes schoolwide programs to fund growth when aligned with comprehensive support and improvement plans.

If your school qualifies as a Title I schoolwide program, teacher capacity building may be your highest-impact use of funds. Strategic investment in evidence-based practices can transform teaching quality.

Many local education agencies operate under outdated assumptions and miss opportunities to address the root causes of low achievement. The real need is to systematically strengthen teacher effectiveness.

Why Invest Title I Dollars in Teacher Capacity Building?

Investing in teacher capacity produces higher returns than class-size reduction, with 2024 meta-analyses indicating that capacity-building interventions yield an effect size of g = 0.792 for teacher knowledge, compared to negligible gains from isolated structural changes.

Teacher capacity encompasses more than subject-matter expertise alone. It includes pedagogical knowledge, strong instructional skills, belief in one’s ability to help students succeed (self-efficacy), and effective classroom management.

High-poverty schools experience higher annual teacher turnover rates and often employ more novice teachers. These environments present greater instructional challenges and more diverse student needs.

A 2024 meta-analysis of 27 studies found that capacity-building interventions produced an effect size of g = 0.614 for perceived capabilities and g = 0.792 for teacher knowledge gains—medium-to-large effects by research conventions.

A 2025 STEM meta-analysis reported an effect size of g = 0.551 for teacher self-efficacy across 18 empirical studies in multiple contexts.

High-quality, data-driven instruction typically produces effect sizes around 0.37–0.38, directly impacting student academic achievement. NeMTSS found that shorter, high-quality professional development produced an effect size of 0.35, while longer, medium-quality programs generated only 0.08, a fourfold difference that proves quality matters more than sheer duration.

A single instructional coach serving 20 teachers costs about $80,000 annually, including benefits, or approximately $4,000 per teacher. Even modest improvements in teacher effectiveness from this investment can substantially multiply returns in student achievement.

Using Title I to strengthen teacher capacity works. Job-embedded professional development and coaching cycles produce results, and sustained support consistently outperforms one-time workshops. Impact compounds year after year as teachers grow.

What Are the Allowable Uses of Title I Funds for Professional Development?

Federal law allows more professional development flexibility than most administrators realize.

ESSA’s language regarding allowable uses is quite flexible. Schools can strategically use Title I for professional development as long as it is evidence-based and tied to identified needs and student outcomes.

- Content-Focused Professional Development Days offer deep dives into content. For example, eight half-day sessions throughout the year can be effective, especially when they include active learning opportunities that allow teachers to practice new techniques.

- Coaching Cycles for Job-Embedded Learning provide sustained support. Observation–feedback–practice loops provide individualized support for teachers. A literacy coach might conduct weekly coaching cycles that include observing lessons, debriefing, modeling strategies, and co-teaching.

- Professional Learning Communities with Collaborative Planning Time structure teacher collaboration. Teams focus on student learning data, and Title I funds can cover substitute teachers to provide release time. Each meeting follows protocols for analyzing student work and planning next steps.

- Lesson Study Cycles involve collaborative lesson design and structured observation. Teachers design lessons together, observe implementation using protocols, and revise based on evidence. This evidence-based practice, adapted from Japan, has documented positive effects.

- Peer Mentoring and Observation Systems formalize peer learning. Experienced master teachers support novice colleagues through structured mentoring, with Title I funds covering stipends for mentors and substitute coverage for observations. These relationships improve teacher retention in high-poverty schools.

- Data-Driven Instruction Training focuses on using data to inform instruction. Training builds skills in progress monitoring and formative assessment and teaches teachers how to use student data to adjust instruction.

- Differentiated Instruction Strategies help teachers meet diverse needs in heterogeneous classrooms, particularly critical in high-poverty schools serving English learners and students with disabilities.

- Classroom Management Professional Development helps teachers establish effective routines and structures. Strong classroom management is foundational for student achievement, and many teachers need explicit support in developing these skills.

Title I can also support paraprofessional development when it is directly linked to instructional support. Training related to small-group interventions, progress monitoring, or curriculum programs that paraprofessionals deliver qualifies as an allowable use.

From a staffing perspective, Title I enables strategic investments in instructional coaching positions, master teacher stipends, and substitute coverage for collaborative planning time.

The “supplement, not supplant” requirement is critical: Title I must add to state and local funds and cannot replace funding that districts are already obligated to provide.

Evidence-based practices are another critical ESSA consideration. Schools should cite research supporting their chosen approaches and clearly document expected effect sizes or evidence levels.

Designing a Title I–Funded Teacher Capacity Strategy

Strategic planning ensures that Title I investments produce maximum impact on teaching quality.

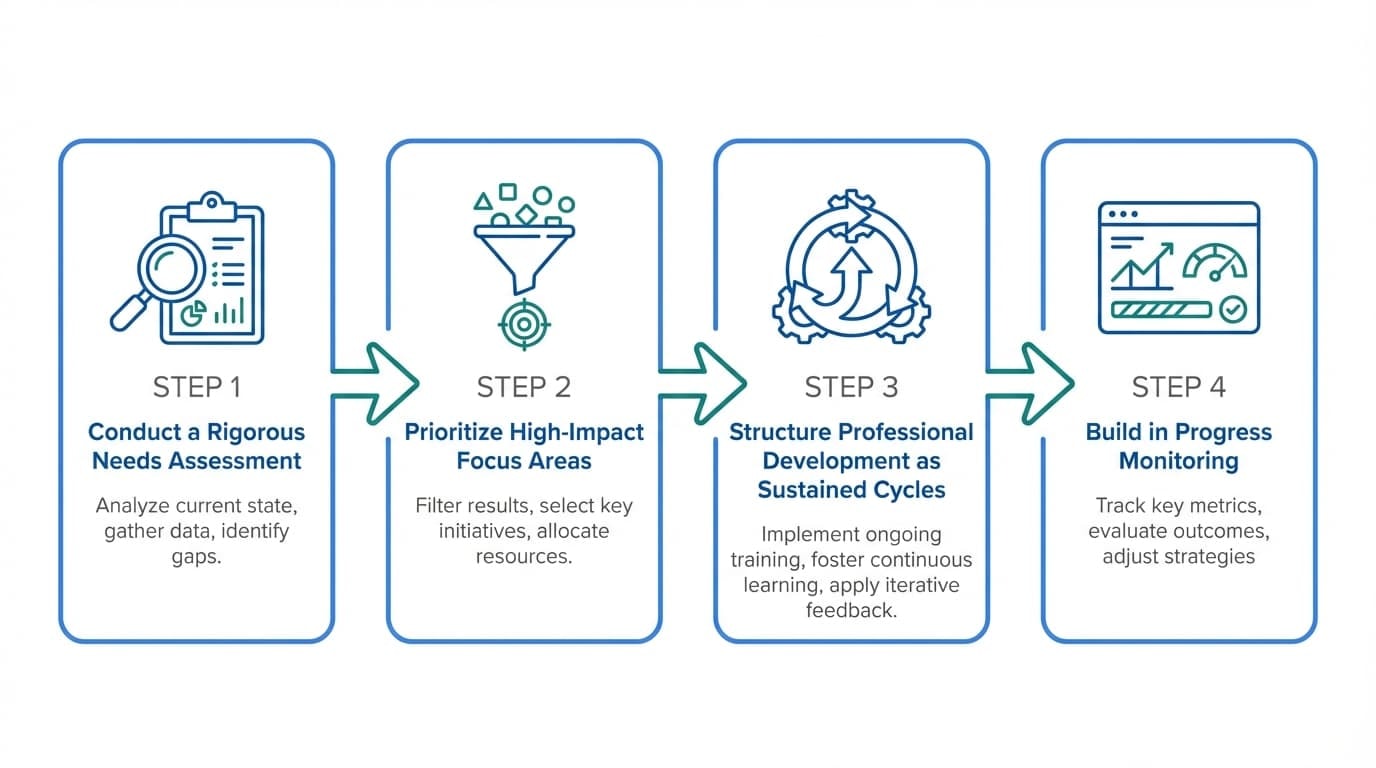

Step 1: Conduct a Rigorous Needs Assessment

Gather data from multiple sources on students and their needs. Collect classroom observation data using validated rubrics, analyze student performance trends on state assessments, and administer teacher self-efficacy surveys to understand confidence levels.

Look for patterns that pinpoint specific capacity gaps. Are teachers struggling with classroom management in particular grades? Is foundational literacy instruction inconsistent across K–2 classrooms? Are English learners receiving adequate differentiated instruction?

The needs assessment should examine current teacher effectiveness using student achievement data disaggregated by subgroups, teacher survey data on professional learning needs, and trends from classroom observations.

Step 2: Prioritize High-Impact Focus Areas

Resist the temptation to spread Title I funds too thinly. Do not attempt to address every identified need at once. Local education agencies that achieve gains tend to focus on a few high-impact areas.

Examples include:

- Foundational literacy instruction in grades K–3

- Algebra readiness in grades 7–9

- Inclusive instructional practices for diverse learners

- Data-driven instruction protocols across all grade levels

- Culturally responsive teaching to build strong relationships with students

Select one or two focus areas for Title I investment and then invest deeply in sustained, job-embedded support over time.

Step 3: Structure Professional Development as Sustained Cycles

Single-day workshops rarely change teacher effectiveness. The Desimone framework recommends a minimum of 20 contact hours distributed across a semester or year. Mix initial learning sessions with coaching cycles, collaborative planning time, and peer observation.

High-quality, ongoing development depends on real-time data about teachers’ implementation progress and student responses. A single August training day will not change practice; sustained professional development with multiple touchpoints throughout the year creates conditions for genuine growth and improvement.

Structure activities across the entire school year, monitor progress, and adjust support based on evidence.

Step 4: Build in Progress Monitoring

Define clear teacher practice indicators to track, and use observation and feedback systems to measure them. Track consistent use of formative assessment and monitor fidelity of implementation for specific evidence-based practices.

Pair teacher practice measures with student indicators. Reading and math benchmark scores can show academic growth, while discipline referrals might reflect improved classroom management.

Schedule regular data reviews in professional learning teams so teachers can reflect on practice and student outcomes. This data-driven approach ensures professional development responds to actual needs.

Progress monitoring should also track implementation quality: Are coaching cycles occurring with the planned frequency? Are meetings focused on instruction, or are they sidetracked by unrelated issues?

Continuous improvement ensures Title I investments get better over time, as each year’s lessons inform refinements to the model.

High-Impact Title I–Funded Capacity-Building Models

The following proven models show how schools successfully use Title I for teacher development.

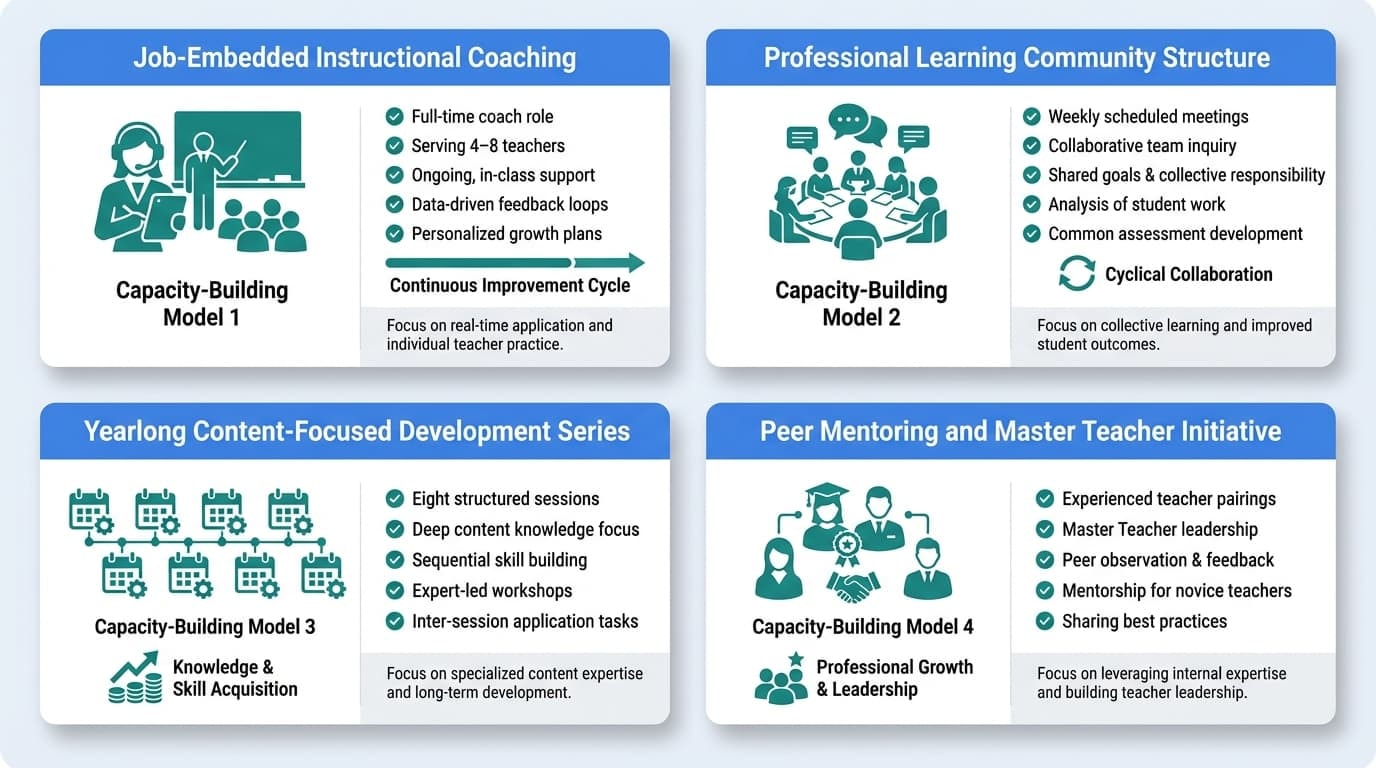

Model 1: Job-Embedded Instructional Coaching

Title I funds a full-time instructional coach serving 4–8 teachers or teams, depending on context. The coach runs weekly coaching cycles: observing lessons on Monday, debriefing on Tuesday, modeling on Wednesday, co-teaching on Thursday, and conducting follow-up observations on Friday.

All coaching is explicitly tied to state standards and specific student learning gaps. The coach documents patterns across classrooms and shares trends with the principal and professional learning teams.

Research shows that coaching produces larger effect sizes than workshop-only professional development models.

Model 2: Professional Learning Community Structure

A Title I elementary school implements weekly professional learning community (PLC) meetings. Title I funds cover substitute teachers to provide regular collaborative planning time.

Each PLC meeting follows structured protocols aligned to school goals: reviewing reading benchmark data for identified students, analyzing which instructional practices work, planning adjustments to Tier 1 core instruction, and designing targeted Tier 2 interventions.

This model creates sustainable learning structures in which teachers build capacity through peer collaboration and the examination of student work. The investment in substitute coverage and stipends helps embed collaborative practices into school culture.

Model 3: Yearlong Content-Focused Development Series

A local education agency designs an eight-session, content-focused professional development program spread across the 2026–27 school year. Reading specialists serving Title I schools participate in active learning sessions incorporating real classroom examples.

Sessions are spaced 3–4 weeks apart, giving teachers time to implement new strategies. The facilitator offers brief email coaching between sessions and reviews implementation artifacts submitted by teachers for feedback.

The series culminates in lesson study cycles in which teachers design comprehension lessons, observe one another, and revise based on student evidence. Title I covers substitute costs, enabling participation.

Model 4: Peer Mentoring and Master Teacher Initiative

Title I supports comprehensive peer mentoring for novice teachers. Each novice is paired with an experienced master teacher. Stipends for master teachers typically range from $2,000 to $3,000, and substitute coverage enables monthly classroom observations.

This model directly addresses teacher retention. Research shows structured mentoring reduces first-year attrition and measurably accelerates the development of teacher effectiveness.

These models share common elements: they are job-embedded rather than one-time workshops, sustained over time, and structured around collaborative planning and feedback.

Coordinating Title I with Title II-A and Other Federal Grants

Smart coordination of federal funding streams maximizes impact and prevents duplication.

Titles I and II serve related but distinct purposes. Understanding the differences enables strategic coordination rather than redundancy.

Title I focuses on improving achievement in high-poverty schools through schoolwide or targeted assistance programs; professional development is one allowable use when tied to improvement priorities. Title II, Part A specifically targets teachers and principals across the entire local education agency.

Use Title II to fund district-wide professional development and basic instructional coaching infrastructure. Then, use Title I to intensify supports in Title I schools by adding additional coaches and providing extra collaborative planning time.

For example, Title II might underwrite core training in classroom management that all district teachers receive. Title I can then layer additional coaching cycles, intensive observation, and feedback systems in high-need schools.

The result is a coherent system in which intensive implementation support flows to the schools that need it most.

State guidance increasingly encourages coordinated planning to maximize allowable uses of each funding source, with careful documentation of which costs are charged to which program.

Measuring Impact of Title I–Funded Teacher Capacity Building

Practical evaluation demonstrates whether Title I investments improve teaching and student learning.

ESSA and state agencies expect evidence of impact on both teacher effectiveness and student academic achievement, not just participation counts from sign-in sheets.

Effective measurement requires intentional evaluation design from the start, not an afterthought once programs are already running.

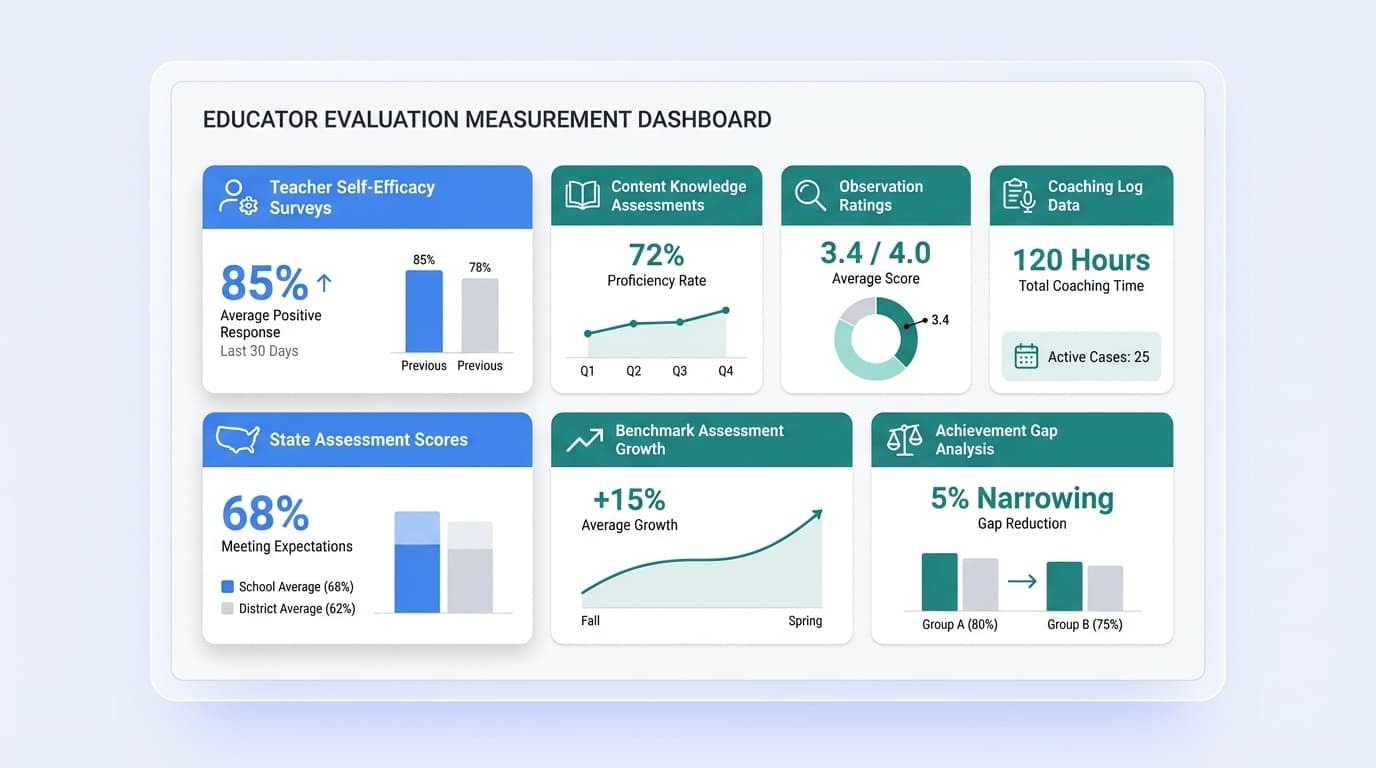

- Teacher Self-Efficacy Surveys measure teachers’ confidence in their ability to impact student learning. Administer validated instruments at the beginning and end of the year and calculate effect sizes showing growth over time.

- Content Knowledge Assessments use pre- and post-tests to document gains in teacher knowledge, potentially reaching effect sizes around g = 0.792.

- Observation Ratings track changes in teacher effectiveness, using the same observation framework consistently throughout the year to look for growth trajectories in key practices.

- Coaching Log Data documents the frequency, duration, and focus of coaching cycles. Analyze whether teachers move from “developing” to higher performance levels over time.

- State Assessment Scores allow schools to compare achievement growth for students whose teachers participated in Title I–funded capacity building to those who did not; effect sizes can help quantify impact.

- Benchmark Assessment Growth provides more proximal measures of student learning, showing whether students display stronger growth trajectories across the year.

- Achievement Gap Analysis is especially important for Title I. Disaggregate all student data by subgroups and document whether gaps are narrowing.

Create logic models that show the hypothesized pathway from Title I–funded activities to teacher practice changes to student learning outcomes. When data confirm each link, you build a strong evidence base.

Build annual reflection into planning by using findings to scale up high-impact models that show strong effect sizes and discontinue low-yield activities.

This data-driven approach ensures Title I continuously improves instructional quality over time.

Action Plan: Implementing Title I–Funded Capacity Building

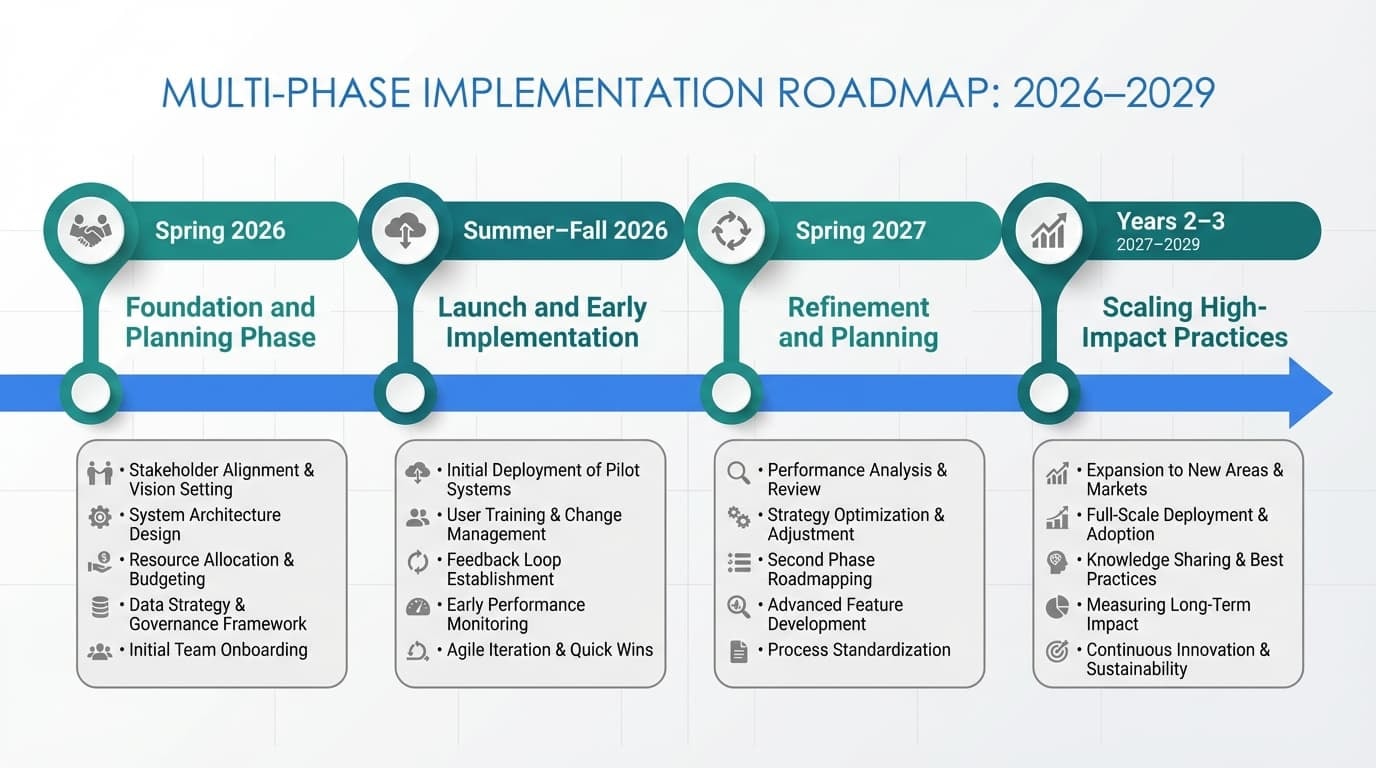

This phased action plan outlines how districts can launch, implement, and sustain high-impact teacher capacity-building efforts using Title I funds. Each phase builds intentionally on the previous one to ensure coherence, compliance, and measurable impact.

Spring 2026: Foundation and Planning Phase

This phase focuses on building a strong instructional and compliance foundation before implementation begins.

- Conduct a Comprehensive Needs Assessment (March–April). Gather multiple data sources to identify priority needs. Review classroom observation data from the current year, analyze state assessment and benchmark data, and administer teacher surveys and knowledge assessments to develop a well-rounded understanding of instructional gaps.

- Engage Teachers in the Assessment Process. Actively involve teachers by asking targeted questions about their instructional challenges, professional learning needs, and areas where additional support would be most valuable.

Using the results of the needs assessment, districts can narrow their focus to the areas most likely to produce meaningful gains.

- Identify 1–2 High-Impact Focus Areas (April). Select a small number of priority areas for Title I–funded capacity building based on the data. Avoid the temptation to address every need at once in order to maintain depth and effectiveness.

Once focus areas are identified, professional learning structures must be intentionally designed.

- Design Professional Development Structures (April–May). Map out the components of the initiative, determining whether job-embedded coaching, PLCs, lesson study, or a combination will be used. Clearly define how each component works together as part of a cohesive system.

Finally, planning must be translated into compliant and well-documented funding decisions.

- Budget and Document (May–June). Align the plan with the upcoming Title I allocation and document how all proposed expenditures meet ESSA’s allowable uses and evidence-based requirements.

Summer–Fall 2026: Launch and Early Implementation

This phase emphasizes preparation, clarity, and consistent execution as the initiative moves from planning to practice.

- Provide Intensive Training (June–August). Prepare instructional coaches and key leaders before the school year begins by ensuring they have deep content knowledge and a strong understanding of the selected instructional strategies.

A strong launch depends on transparent communication with staff.

- Launch with Clear Communication (August). Clearly explain the initiative’s purpose to all staff, emphasizing that professional learning and coaching are designed to support growth rather than evaluate or penalize teachers.

With expectations established, districts can move into active implementation.

- Implement with Fidelity (September–December). Execute all planned activities as designed. Instructional coaches conduct regular coaching cycles, and PLCs meet consistently with agendas grounded in student data and instructional practice.

To monitor early progress, districts should pause for a structured check-in.

- Conduct a Mid-Year Review (December–January). Analyze leading indicators such as observation data and benchmark assessments to determine whether teacher practices and student outcomes are trending in the desired direction.

Spring 2027: Refinement and Planning

This phase focuses on adjustment, evaluation, and preparation for sustained improvement.

- Intensify Support (January–March). Use mid-year data to provide additional coaching or targeted supports for teachers who need it, differentiating Title I–funded services as appropriate.

As implementation concludes, comprehensive data collection becomes critical.

- Collect End-of-Year Data (April–May). Administer post-surveys to measure teacher self-efficacy, compile observation ratings that demonstrate growth in instructional effectiveness, and analyze state assessment results for students in supported classrooms.

This evidence informs decisions for the following year.

- Plan Year 2 Refinements (May–June). Identify strategies that produced strong results and should be scaled, as well as those that yielded limited impact despite strong implementation.

Years 2–3: Scaling High-Impact Practices

In later years, the focus shifts from initial implementation to sustainability and expansion.

- Expand Effective Models. Increase the reach of instructional approaches that demonstrate strong evidence of impact on teacher practice and student learning.

- Develop Internal Capacity. Cultivate teacher leaders and master teachers who can sustain and extend the work over time, reducing reliance on external support.

- Coordinate with Other Funding Sources. Use Title I to provide intensive supports in high-poverty schools while leveraging other funding streams, such as Title II, for districtwide initiatives.

- Build Evidence Over Time. Collect multi-year data demonstrating consistent gains in teacher practice and student outcomes, creating a compelling case for continued Title I investment in teacher capacity building.

Conclusion: Maximizing Title I’s Potential for Teacher Excellence

Continuously evaluating impact on both teacher practice and student academic achievement using multiple measures ensures that Title I funds are truly improving outcomes for students.

The allowable uses are clear under ESSA, the research base supporting teacher capacity building is strong, and the funding reaches roughly 90% of districts. What remains is a firm commitment to leverage Title I for its highest purpose: building teacher capacity so that every child in a high-poverty school learns from highly effective educators who are continually improving their practice.

Frequently Asked Questions

Have questions? We’re happy to help!

What documentation is required to audit-proof a Title I instructional coach position?

To satisfy supplement-not-supplant requirements, districts must maintain job descriptions ensuring the coach’s duties are distinct from state-mandated roles, along with Time and Effort logs verifying that 100% of the coach’s schedule is dedicated to Title I targeted activities.

How do we document that our Title I-funded professional development is “evidence-based”?

Start by identifying research supporting your chosen approach. Document the evidence level under ESSA’s tiered framework. Cite meta-analyses showing positive effect sizes.

Create a logic model connecting professional development activities to expected teacher outcomes and, ultimately, to student results. Reference What Works Clearinghouse or peer-reviewed studies.

For each major initiative, specify the evidence tier: strong, moderate, promising, or demonstrates a rationale.

What’s the difference between using Title I and Title II for teacher professional development?

Title II, Part A exists specifically to support teachers and principals and can fund a broad range of development across the local education agency, regardless of student demographics.

Title I focuses on improving achievement through schoolwide or targeted assistance programs. Professional development represents one of many allowable activities when tied to improvement priorities.

Use Title II for districtwide initiatives. Use Title I to intensify support with additional coaching beyond the districtwide baseline.

When should we begin planning Title I professional development for the 2026–27 school year?

Start in early spring 2026—ideally March—to allow adequate time for thoughtful planning. Use your comprehensive needs assessment data from the current year to set priorities for the upcoming year’s capacity-building initiatives.

By May, identify focus areas for Title I–funded professional development. Outline specific professional development structures you will use. This timeline allows you to incorporate details into the Title I application and budget before the new year.

Can paraprofessionals participate in Title I-funded professional development?

Paraprofessionals can participate when the development addresses needs identified in the schoolwide plan. Training may include small-group intervention techniques and curriculum programs that paraprofessionals deliver to students.

However, general professional development unrelated to their instructional role would not meet Title I requirements. Training must specifically address how paraprofessionals support students’ needs in Title I programs.